I find myself quite astonished to see my current emotional state appearing on the page through what my characters are saying—and this without intentionality. I’m not journaling my feelings then transferring them to the characters, though I advocate that method when I wear my teaching hat. Except right now, buried in my writing hat, it’s as though my characters are feeling for me, then shouting feelings out until they smack me in the face.

Perhaps it’s best if I explain. I’m waiting on decisions from people I don’t know, people who, it feels to me, hold keys to my professional future. Any writer will recognize this feeling when sending work out into the world to be judged for its literary merit, its marketability, its potential to find a readership among the audience the publishing professional serves. It needn’t be memoir for this vulnerability to occur. Fiction needn’t even be autobiographical to be a blueprint of the writer’s psyche. How can it be any other way when the author’s choices rule the day, godlike in creation? This is my world, says the author. These are the people in it. These are the rules and how they work. This is what it means.

No matter whose name I put on it, whose world could I possibly create besides my own?

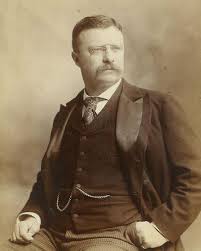

To garner up the courage to submit, one reads that blessed guru of hopefulness, Elizabeth Gilbert, as she tells us in Big Magic we can choose what to believe about the writing process and about our work. One reads Brene Brown in Daring Greatly, quoting Teddy Roosevelt telling us to get out of the stands and onto the playing field, in short—to submit!

But I don’t truly know how I’m feeling until Albert Einstein, in fictional form, writes this letter to his affianced:

My dearest little Sweetheart,

To soothe my despair on returning from our parting, I picked up my violin. How is it that in counting beats, whether quarter notes, eighth notes, dotted halves, or triplets, while I am giving each their due, hours disappear, as completely present as they are completely absent? I lose myself in music and didn’t notice when Maja entered, until she placed a letter on the music stand. Canton of Bern was written on the envelope. My bow froze. The envelope was much too thin to bring good news and how I wished it hadn’t come! Better to hold out hope than to be rejected. I told Maja she might open it, while my frustration spoke in my bowing notes forte that were marked piano. She frowned as she was reading. I dragged my bow across the G and D strings, producing the most godawful sturm und drang. After all this time, and myriad rejections, I no longer can imagine being welcomed in with open arms.

Let’s be clear: I wrote that letter. It’s true that Albert Einstein’s love letters exist, though a century passed between their writing and their publication. That said, I’m not quoting them. The practical reason is that I choose not to contend with the legality of the permission process and possible expense. The literary reason is their content doesn’t always serve my text.

That is not to say I’m not guided by them. I am. As I am with facts. We know, for example, that Albert Einstein played the violin (as I did in childhood, albeit briefly). We know that when he felt stymied in his head, the music opened up the possibilities for him. We also know that when he graduated from the ETH in Zurich, he applied for many jobs for which he was rejected. But as to how he felt when yet another rejection letter came? He’s telling me how I feel. How afraid I am to hope. Why I don’t doggedly pursue those who show interest in my work. Because if the answer will be no, perhaps I can better maintain balance, keep writing into ether, if I don’t know.

So, what am I to do with this?

This morning I read this bit by Richard Rohr:

… my simple definition of suffering: when you are not in control.

…

Suffering, of course, can lead you in either of two directions: It can make you very bitter and close you down, or it can make you wise, compassionate, and utterly open, either because heart has been softened, or perhaps because suffering makes you feel like you have nothing more to lose.

–Richard Rohr, The Naked Now, 123-125 (selected)

So, as I suffer, Rohr is telling me my choices. That choice is always up to me. Which puts me in control.

When I finish writing this brief essay, I will return to my characters. In that scene I’m writing now, who is feeling out of control? (Is it fair to say that if no one is, the scene is not bearing its own weight?)

Which choice will my character make?